Water is the third and most accomplished film in director Deepa Mehta’s Elements Trilogy, which consists of three films that are thematically linked together rather than being films with an ongoing story and reoccurring characters. Water is set in 1938 in the holy city of Varanasi, which is situated in India on the banks of the Ganges, a sacred river in the Hindu religion. The film is unusual for having three protagonists – Chuyia (Sarala Kariyawasam), Kalyani (Lisa Ray) and Shakuntala (Seema Biswas) – all of whom are widows. Due to very conservative interpretations of Hinduism, the three women are expected to live the remainder of their lives in poverty and chastity in a segregated temple with other widows from the area. As widows they are regarded as spiritually unclean and an economic burden on their families and society.

In the background to their stories is the beginning of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s campaign to drive the British out of India and establish an independent India movement through non-violence. The hope and progressive thinking that Gandhi introduced into Indian society provides a stark contrast to the sad and oppressive lives that the widows must endure. Through the lives of the three main characters, Water exposes and comments on the appalling treatment of widowed women in some parts of India, since even today the attitudes that are depicted in the film in the 1930s still exist. It also uses the treatment of the widows to represent larger issues about how religion is misused by people in a position of power to deny human rights.

While specific colours dominate all the Element Trilogy films, the use of white and blue in Water is especially important in the way the film engages with notions of purity. In the context of the film white is both the colour of mourning and traditional notions of purity. This makes it a particularly oppressive colour since the widows do live a death-like existence due to religious instruction to remain chaste out of respect for their deceased husbands. This concept of purity is aligned in the film with religious hypocrisy designed to keep the widows subservient since doing otherwise would mean caring for them properly and therefore having to spend money.

Blue is the colour of water, which has the power to give life and to take it away. Furthermore, in Hindi water represents feelings, intuition and imagination, which are all characteristics that are traditionally associated with femininity. This is appropriate since the film is about women and the way women are expected to behave. However, when removed from the motif of water, the colour blue is used in Water to challenges the dogmatic representation of purity as self-denial and obedience. Rather than following a set of social and religious rules designed by people in power, expressions of true love and compassion are presented in Water as true moments of purity and these moments are evocatively associated with the colour blue.

Deepa Mehta and the Elements Trilogy

Deepa Mehta was born in India, but migrated to Canada in her early twenties. Her films draw upon both western cinematic traditions and Indian customs to pursue a feminist ethical agenda. She explores power structures in Indian society, both historical and contemporary, to critique the inequality created through gender discrimination, religious hypocrisy and class. Mehta first received international prominence in 1996 with the release of her critically acclaimed and highly controversial Fire, which was the first film in the Elements Trilogy. The same-sex relationship themes caused considerable unrest from many conservative religious groups and political parties that even resulted in a cinema being burnt down. The hostility towards Mehta from groups within India meant that production for Water was shut down in 2000 when protestors destroyed the sets the night before shooting began. Mehta had to relocate production from the banks of the Ganges in India to Pakistan and the film could not commence shooting until 2005.

The common themes in all the films in the Elements Trilogy are religion being misused for political purposes, women being made subordinate, the oppression of female desire and forbidden love. In Fire the forbidden love is between two women and Mehta explores the politics of sexuality not just between the same-sex couple, but within the dynamics of two passionless arranged marriages. The second film in the trilogy is Earth (1998) set in 1947 during the dissolution of the British Indian Empire. It was a time of enormous religious tension between the Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims as 12.5 million people were displaced as geographical divisions were formed based on religious demographics. The nature of forbidden love explored in Earth is between a man and woman with different religions, with Mehta exploring the politics of nationalism and how this can manifest in religious extremism and violence. In Water the forbidden love is the widow Kalyani falling in love with another man, which is seen to be an act of betrayal against her dead husband. Mehta explores the politics of religion to highlight how religious hypocrisy is used to ensure women are undermined and made subservient for economic purposes.

Chuyia

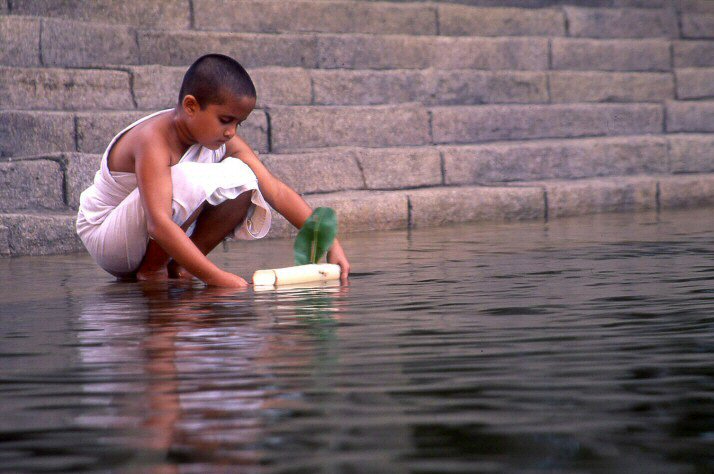

The first of the three protagonists in Water is Chuyia, a child who has become a widow as a result of an arranged marriage to a man she never met. At the beginning of the film she is presented as something of a free and rebellious spirit despite the absurdity and unfairness of the situation she is placed in. Happily eating a sugar cane she is introduced gleefully playing with the feet of her dying husband as he is being transported. It is not until the reality of having to live in the widow’s temple sinks in that she displays any actual signs of grief and the contrast between her colourful and decorative clothes to the white robes she is forced to wear is very pronounced. However, even once in the temple Chuyia stands out as a force of life with her head painted by Shakuntala in bright yellow turmeric and the flurry of quick edits as she runs through the temple, providing a playful and disruptive break to the static and slow camera movements that are otherwise used within the temple.

The sense of playfulness within Chuyia is expressed throughout the film through her constant movement and the movement of the camera during many of the scenes she is featured in. Her catatonic stillness during the film’s conclusion is therefore devastating to witness. What happens to Chuyia comments on the dual symbolism of the Ganges in the film to purify and to take away life. While the Ganges is the site for purification for Hindu people, it is also the passage to the upper class homes where Chuyia is tricked into prostitution. It is fitting that Chuyia’s escape from Varanasi is in the arms of Narayan (John Abraham), whose father has committed so much damage, and by train. While water is traditionally a symbol of change and progression, in Water the Ganges ultimately becomes like institutionalised religion – a destructive force that destroys lives while continuing the pretence of being about purity. The train on the other hand is a force of modernity and progress that takes Chuyia and Narayan into Gandhi’s new India and away from the oppressive traditions and abuses of power in Varanasi.

Kalyani

Chuyia isn’t the only character who is harmed by the Ganges as Kalyani is literally killed by it when she drowns herself after being denied marriage to Narayan, ironically by his father who had been using Kalyani as a prostitute before turning on Chuyia. Throughout Water Kalyani is compared to Chuyia as an older version of the woman Chuyia may have become if she stayed in Varanasi. Kalyani is also a widow who was married to a man she never met and she was being prostituted by Madhumati (Manorama), the exploitive older widow who runs the temple. When Kalyani’s long hair is cut off by Madhumati, who presumably only allowed Kalyani to grow it long in the first place to appear attractive as a prostitute, the scene mirrors the earlier scene when Chuyia’s hair is cut before she enters the temple. The graphic matches establish the strong relationship between Kalyani and Chuyia, and the danger of Chuyia sharing the same fate.

Kalyani’s religious devotion is important to note as being different from the misuse of religious rhetoric that is seen throughout the film. Mehta is not attacking religion in Water but critiquing the way it is used for economic and political gain. Kalyani’s faith and charity represents religion in its purest and most noble sense. She compares herself to a lotus flower, which is a divine symbol in ancient Asian traditions representing the virtues of sexual purity and non-attachment. When Kalyani first appears in the film she is shot from a low angle so she majestically appears above the rest of the temple. Chuyia even momentarily thinks that she is an angel. Kalyani is also shot from a similar low angle during the various scenes with Narayan, although scenes when she is in the temple and he is on the street are often framed so she appears behind the bars on the balcony to give the impression of her being imprisoned.

Kalyani is also strongly associated with the colour blue and says when she remarries she will wear blue, the colour of Krishna. Blue is not only a colour commonly used to represent water, but in the film is the colour of life and associated with characters during moments of spiritual transformation. The very romantic sequence when Kalyani sneaks out to be with Narayan features a heavy use of blue light and blue backgrounds to indicate the purity, in the true sense, of the love that has developed between the pair. In this way blue is used in the film to symbolise falling in love as an act of spiritual transformation. The other major use of the colour blue for a moment of spiritual transformation is associated with Shakuntala in the moment when she follows her conscience despite it so significantly conflicting with her religious beliefs.

Shakuntala

The moment when Shakuntala is bathed in a blue light is when she directly stands up to Madhumati to free Kalyani. Up until that moment Shakuntala had been an enigmatic character. She is another widow at the temple, somehow above Madhumati’s authority but until this moment had never directly challenged her. Even more so than Kalyani, Shakuntala displays a sincere devotion to her faith that frequently manifests through her taking on a nurturing role with some of the other widows including Chuyia and Kalyani. While something of a peripheral character during most of the film, which focuses on Kalyani through the eyes of Chuyia, Shakuntala emerges as the final protagonist when she directly confronts the religious rhetoric that she has been living by to make sure Chuyia leaves Varanasi so that she won’t be abused again.

Towards the end of the film, possibly as a result of witnessing what was happening to Kalyani and Chuyia, Shakuntala begins questioning her faith. This culminates in the scene when she confronts the priest Sadananda (Kulbhushan Kharbanda) about the scriptures concerning widows. A sympathetic character, Sadananda explains that the relevant scriptures do list a life of self denial as one of the options for widows, along with being burned with her husband or marrying the husband’s younger brother. However, he also reveals that there are now new laws in favour of remarriage, but religious groups have ignored these laws since the laws do not suit them. This is a crucial scene in the film since it directly addresses the danger of religion having too much power and influence to the extent that it can bypass the law for its own end. It also exposes how religious beliefs can be hijacked to serve the needs of people in a position of authority.

Water concludes with Shakuntala performing an extreme act of kindness, generosity and sacrifice by saving Chuyia from the widow’s temple and Madhumati’s clutches. The audience are not completely certain about what Shakuntala’s risks by doing this, but it is a reasonable assumption that by defying Madhumati and the local customs Shakuntala will at the very least be cast out of the temple to fend for herself in an environment hostile towards widows. Her act of defiance is also one of religious defiance against a set of powerful beliefs she had lived with her entire life.

It is significant that Shakuntala takes Chuyia away from the Ganges, and all it represents, to the train and other symbols of progress. Not only is Ghandi, who is on the train, a symbol of the future but he speaks into a microphone, which represents new modes of mass communication that would allow messages such as his to travel further than they ever had before. As a member of the new generation of Indian people, Chuyia has a chance to reap the rewards of these changes so ‘escapes’ on the train with Narayan who by accepting the responsibility of looking after her is somewhat redeemed from his previous passivity and inaction. On the other hand, Shakuntala is left behind, with the train receding into the background, as she is trapped in an old way of life. Water ends with the arresting and provocative image of Shakuntala starring into the camera in a mixture of sorrow, hope, despair, uncertainty and defiance. Her bold glare into the camera could even be read as a challenge to the audience to confront the injustices within their own lives.

Originally published in issue 64 (Summer 2012) of Screen Education.