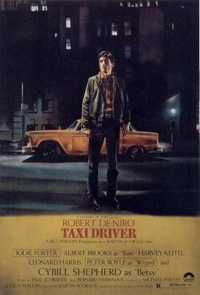

In 1983 director David Cronenberg curated a science fiction retrospective for the Toronto Film Festival and his provocative selections included Martin Scorsese’s 1976 masterpiece Taxi Driver. In the program notes Cronenberg explained this choice by describing Taxi Driver as:

In 1983 director David Cronenberg curated a science fiction retrospective for the Toronto Film Festival and his provocative selections included Martin Scorsese’s 1976 masterpiece Taxi Driver. In the program notes Cronenberg explained this choice by describing Taxi Driver as:

[A] better Blade Runner than Blade Runner. New York is a nightmare LA/Tokyo of the future. De Niro is a sleepless alien who does a poor job as passing himself off as an earthling. He can’t really figure out human sexuality but he wants to get involved anyway. It doesn’t work.

It’s as good a reading of Taxi Driver as any since it captures the extent to which Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle character is something of an impressionable outsider in the urban jungle of New York. A Vietnam vet working long hours as a taxi driver due to his insomnia, Travis is a product, victim and observer of late 1970s America, but also a terrifying force of violence, determined to ‘wash all this scum off the streets’. Scorsese’s subjective camera follows Travis and his taxi through the streets of New York as he searches for a human connection, fails and then takes the role of a very confused avenging moral crusader, culminating in the film’s still shockingly violent ending.

Travis is locked in an infantile state that is suggested throughout Taxi Driver in his speech, limited comprehension and xenophobic curiosity/paranoia towards African Americans. Like so many soldiers trained to fight in Vietnam, as depicted over ten years later in Full Metal Jacket, he seems to have had his personality stripped away, leaving him as a blank slate with a simmering, barely repressed rage. In later scenes when he does give himself a purpose beyond mere existence, the ticking clock sound on the soundtrack is accentuated to mimic the sound of a time bomb.

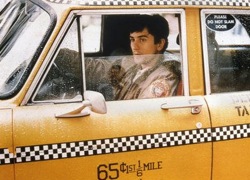

As the opening chords of Bernard Herrmann’s brilliant (and sadly final) score crescendo over the soundtrack during the opening of the film, we see Travis’s taxi emerge into the cinema frame out of a cloud of steam as if it is being born into the world of the film. Throughout the film Scorsese shoots both Travis and his yellow taxicab from every angle possible, ensuring all components of the man and the machine get their own close-up at least once. They are one and the same; cruising the less desirable parts of New York like a predatory animal and slowly being changed by the city. The taxi picks up dents from hurled objects and stains from the passengers in the back seat, Travis picks ups some disturbingly peculiar ideas about women.

Without any family of his own Travis searches for substitutes. Turning to the senior taxi driver Wizard (Peter Boyle) for some kind of fatherly advice turns out to be futile as all he gets is an almost comically useless pep talk. Travis projects purity upon Betsy (Cybill Shepherd), seeing her as a perfect woman who may be his lover and in Oedipal terms his substitute mother. Not long after the scene where Betsy spurns him Travis encounters a passenger (played by Scorsese) who delights in telling him about his intent to murder his cheating wife. Ever impressionable, Travis channels this misogynist fury into his feelings of rejection from Betsy and plans to hurt her by assassinating the politician (and alternate father figure) she is campaigning for. Finally, Travis encounters child-prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster) and this time takes on the role of protective father/potential lover towards her, which involves confronting her pimp Sport (Harvey Keitel), another father figure.

And what of the peculiar ending? Is it a cynical joke by Scorsese about how cinema celebrates the use of violence to restore order or is it a sort of delusion dream sequence where Travis imagines an idyllic outcome that vindicates his actions? The camera filming the haunting aerial shot over the room where Travis’s rampage ends then seems to float down the stairs of the building and out into the night as if his soul is departing. It’s a deliberately ambiguous ending, but the outcome is that the film ends with the audience in Travis’s world. A montage of shots of the city streets at night evoke his collapsed reality and the final sudden glare he gives to the camera suggests that wherever he is – in the physical or imagined world – he could snap at any moment.

And what of the peculiar ending? Is it a cynical joke by Scorsese about how cinema celebrates the use of violence to restore order or is it a sort of delusion dream sequence where Travis imagines an idyllic outcome that vindicates his actions? The camera filming the haunting aerial shot over the room where Travis’s rampage ends then seems to float down the stairs of the building and out into the night as if his soul is departing. It’s a deliberately ambiguous ending, but the outcome is that the film ends with the audience in Travis’s world. A montage of shots of the city streets at night evoke his collapsed reality and the final sudden glare he gives to the camera suggests that wherever he is – in the physical or imagined world – he could snap at any moment.

An urban fusion of themes and images from the western, film noir and, if you agree with Cronenberg, science fiction, Taxi Driver is a brilliant study of alienation, obsession, paranoia and perverse desire. There’s an undeniable power and grittiness that very few films have come close to capturing since. Perhaps it’s the dangerous vicarious and visceral thrills that Travis’s actions provide. Scorsese shows us the world through Travis’s eyes and like with Alex in A Clockwork Orange we rationally condemn such an unhinged individual who is all too ready to respond to the aggressive stimuli around him. However, once we’ve seen the world the way Travis sees it, on a purely emotive level there is something disturbingly seductive about God’s lonely man and his deranged crusade. In this regard Taxi Driver is dangerous cinema and it’s all the better for it.

![]()

For those of you in Melbourne, a new digital restoration of Taxi Driver will be screening at Cinema Nova from Thursday 7 July 2011 and at The Astor Theatre from Sunday 14 August 2011.